Saturday, July 11, 2009

Thursday, July 9, 2009

Action Plan

ir. Marc Koehler, Lecturer, TU Delft

Sampling and Improvisation

Part 1: Sampling and Reconstitution (Week 1)

In the context of our "remediated” culture, how do we consider the making and the influence of the existing environment? How do we approach the reading of what is occurring in a place? In the first part of the exercise, we will employ the technique of sampling. Here the sampling first refers the undifferentiated collection of “stuff” relative to the time and the place.

The group will engage in the “alternative” (aka unofficial) reading of El Carmel relative to the thematic pairs introduced in the opening presentation. The group will conduct an investigative exercise in which it will collect and piece together what is perceived to be the evidence of certain activities and conditions inherent in El Carmel. This exercise is not about the so-called real but about what appears to be, or simply what is there.

The sampling may contain several types of found objects (similar to collecting souvenirs): material/physical things, images, imprints, sounds/noises, stories, encounters, etc. Here the idea of sampling is closely connected to the time, the paths and the places we will encounter as outsiders. All samples should be registered in a form of mapping in such a way that it provides a personal reading of the place in an impressionistic manner. The five thematic pairs should provide the direction of the sampling process in five layers. Prior to the sampling, a simple navigation plan should be made, for instance by defining a clear path, the landmarks and/or references.

Next, the group will engage in a differentiation process akin to a kind of forensic/archaeological speculation. This process involves piecing together what has been found and the determination of certain taxonomy. This collection of found objects in five layers from the area should be arranged and integrated into three-dimensional re-construction of events and relations. In this process, the group will be engaged in the construction of the perceived conditions that will suggest particular modes of navigation and reading of the place. Both the mapping and the re-constituted object should provide a specific structure of organizing the information. It is crucial to differentiate and reflect the modes of codification, namely: iconic, verbal, tectonic, presentational and temporal. The objective in the first week of the exercises is to produce an analogical space in which improvised relations and objects (design proposals) can be inserted in the part two of the exercise.

As a conclusion of the first part of the exercise, the 3-D construction should be discussed and interpreted in terms of geno- and pheno-conditions. Here the geno-conditions refer to those that occur in a natural course of development or something that is already built into the system (i.e. the genetic, the body, the Dionysian). On the other hand the pheno-conditions refer to something that is intentionally idealized and made (i.e. the cultivated, the signification, the Apollonian). [Also see

The part one will conclude with three products on Wed. 15 Jul.:

a) The map showing the navigation and discovery process in five thematic layers (i.e. one member=one layer)

b) The differentiation and registration of the found objects in relation to the five thematic layers

c) The analogical model in an integrated 3-D re-constitution (a collaborative group work)

Part 2: Improvisation and Composition (Week 2)

Using the construction and the map from the part one, in this part the group will engage in the production-by-improvisation.

Here the improvisation can be summarized as follows:

1. Finding and identifying contingent conditions (between the lines) and “filling in” such contingencies

2. Adding redundant elements responding to (and potentially subverting) the existing condition and its flows

3. Speculating on the assumptions of a certain ideal and acting on it

4. Privileging performed conditions rather than (and in contrast to) the composed ones

5. Producing temporal elements rather than the assumptions of the eternal

6. Eventually creating the objects of performance that may be able resist and to escape the caprices of the dominant order

Despite the flash headlines, the central question here is how we would read and respond to our built environment that has increasingly become contingent and radicalized. It has been said that our contemporary society, in all of its cultural, political and ideological dimensions, functions based on the notion of contingency. Here the term contingency can be understood as a condition in which the criteria of a decision making process involve neither true nor false and therefore logically indeterminate. At the same time the notion of contingency may also be composed of a set of assumptions (what-if’s) that may be neither right nor wrong in a given place and time. It has been also said that in this process we also experience the radicalization of existing historical ideology and its worldview. In the radicalization process, we see the creation of excessive disparity (i.e. the rich and the poor, the strong and the weak, the large and the small, etc.) and the intensified fortification of the given ideology (i.e. capitalism vs. socialism, conservatives vs. liberals, Christians vs. Muslims, legal vs. illegal, natives vs. the immigrants, etc.)

If we were to adopt such a contingent position for the sake of an architectural experiment during the workshop, what are such conditions in El Carmel and how to we perform the act of architecture? Can we clearly ascertain that what we plan and construct as architects will make a difference? To that end, what are our choices: opening up to the contingencies of the daily mundane or radicalizing the desire for certainties?

Part 3: Conclusion

At the end of the workshop period, the group is expected to produce “improvised” insertions and constructs that will respond to and potentially express the contingent conditions found in El Carmel. Central to this process is the improvisation of analogical objects that are born from the reading of the current composition of the area.

The presentation format will be discussed and decided in course of the workshop.

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

Improvising Architecture

Primeval Human Nature or Future Strategy: The Dutch Context

In the history of architecture, the idea of city planning starts with politics. The idea of planned cities dates back to the Greek city, a political city (polis = city = politics). Planned cities are triggered by the need to control the effects of urban population growth (Cerda), to create social stability (Hausmann) or due to the need to sustain economic growth and safety or for the general well-being of the population.

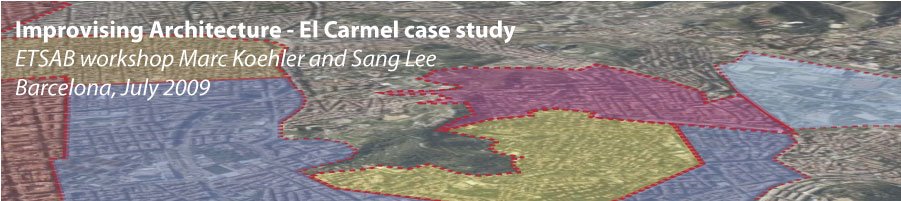

However, the idea of the unplanned city obviously precedes a planned one and is thus closely connected to our primeval organization. Long before human civilization appeared, people built informally constructed settlements that flexibly responded to natural conditions and their social-economic demands. Even today, unplanned cities grow ‘organically’, dealing with complex spatial orders as a result of a temporal process of social and physical negotiation between men, space and nature. Unplanned suburbs, such as El Carmel in Barcelona, present an interesting case for research as they exemplify the urban field conditions where the domestic, the urban and the natural interlink most directly and spontaneously.

The fastest developing unplanned cities we see today sprout from a rapid and uncontrolled growth of urban populations, something most apparent in the cities of still developing countries. Rem Koolhaas states, “… In the context of this hyperdevelopment, the traditional architectural values - composition, aesthetics, and balance - are irrelevant. The speed of international demands is completely out of pace with the ability of traditional designers to respond; construction has left architecture on the sidelines…” Rem Koolhaas, Wired 8.06

There has always been a tension between the planned and the unplanned, the formal and the informal. The border between these urban conditions is, besides a physical border, often political, cultural and economic. In ancient cities, unplanned areas were often occupied by those who were not recognized as legitimate citizens. In Rome, the zone of the unplanned city, just outside the walls of the city, was a marginal zone, occupied by those who were marginalized from the society. It seems this was also the case for El Carmel, an area grown spontaneously in a clandestine development in the 2nd half of the 20th century, as a result of the rapid growth of the urban population of Barcelona. What is the socio-cultural value of these kinds of marginalized areas for the city as a whole? Do we suppress these areas or do we try to enhance its vibrant nature? If so, how can do we enhance them? How do we balance the tension between the political and economic forces that try to incorporate the unplanned into the planned (gentrification) and the forces that resist this? Can architecture play a role in creating this balance?

While unplanned areas tend to become transient and therefore more politicized and planned as they mature (i.e. gentrification), planned cities tend to resist change and therefore stagnate. In return, unplanned cities are open to change, thrive on it, and adapt to it. The strength of the unplanned is its capacity to improvise and the qualities expressed through such improvisation.

By studying these complex informal urban systems, we, architects and planners, can develop design strategies of improvisation in order to benefit and engage the underlying vibrant impetus of urban development. We therefore propose to investigate the potentials of improvisation as a design technique and improvised spaces as the theme of this year’s ETSAB workshop. Can we, by studying the unplanned, adopt principles of improvisation useful in the planning and design of new areas and the re-design of old ones? What can we learn from improvised architecture?

The Netherlands; 100% planned

While looking for Dutch counterparts to El Carmel, we learned that the Netherlands is one of the most planned countries in the world and therefore unplanned urban situations are hard to find. Since the sixteenth century, planning cities has been a way to provide social stability in a complex multicultural society composed of different social, cultural and religious groups, referred to as the Polder model. It is therefore often said that, compared to other countries, the Netherlands does not really have a tradition of urbanism that responds to unplanned growth and marginalized cultures. The effect of this on the Dutch urbanism is visible in the absence of terrains vaques or urban voids, and an intensive and coordinated use of every square meter of open space.

The Dutch tradition of integrated city planning also arose from another pragmatic motive to provide protection from encroaching seawater. The Dutch tradition of city making therefore closely relates to the history of water-management for the cities and their surrounding landscape. Fields around cities had to be drained in order to grow food for the urban population. This was done by complex canal and road systems and with windmills, which provided a shared objective for everyone to collaborate on a regional level to plan the cities. The Polder model planning provided the urban infrastructure on a regional scale, and an efficient economic system, which brought economic prosperity, reflected in many cities such as Amsterdam. In modern Dutch cities, planning was inspired by social-economic and technocratic motives, closely related to the principles of the CIAM doctrine. The CIAM era created another kind of planning, which created a new kind of relationship between people and cities. These areas were so over planned in a top-down manner that they became anonymous environments in which people became alienated due to a lack of possibilities to participate in the political process and building process that structured their living environments. The recent trend is to integrate urban plans in which private initiatives flourish and people can built their own houses as a way to involve them in their surroundings; a new kind of socio-economic consensus model that balances the public and private interests. Because unplanned urban forms hardly exist in the Netherlands, the Dutch team analyzed the relationship between the planned and the unplanned in a more conceptual way.

Approach to the Dutch case study: improvised spatiality:

First we questioned how planned spaces in the Netherlands are appropriated in an unplanned way. Here, improvisation results in aesthetically and functionally more interesting, complex and layered spaces. Next, we analyzed how spaces with an originally unplanned character are increasingly re-regulated as a result of gentrification, commercialization or other economic or political factors. Here, the qualities of improvised, immediate spaces are lost due to over-design and excessive urban regulations.

We will briefly show some examples common in the Netherlands in this regard, based on five polarities of keywords related to the concept of improvisation and improvised spaces.

1. legal – illegal

2. formal – informal

3. authentic – fake

4. personal – anonymous

5. controlled – uncontrolled

Each concept pair is illustrated for a specific location that exemplifies recent/actual phenomena in the urban and architectural production of the Netherlands. We used photographic comparison of before-after situations. The aim is to show the temporal transformation as an essential quality of improvisation. In this regard the systems of regulatory control and top-down design represent a a situation counter to improvisation.

1. legal-illegal: the relation between architecture, tourism and regulation

The red light district Amsterdam represents both a quality as well as a threat for the quality of living. The unregulated zones of the district used to give Amsterdam its special character, but due to mass-tourism, it has lost its initial character and become a contrived sex-mall. The municipality tries to change the area now into a more gentrified zone for the so-called creative business. The city’s official position treats the problem of both marginal space and its tourism as a threat as well as an opportunity for qualitative urban development. The tourism results in the commercialization of public space, which can threaten the integrity of the place and its character that has been accumulated over many centuries. The analysis also takes in account the ideas presented in Spaces of Transgression by Bernard Tschumi.

2. formal-informal: the changing nature of the public domain from the heterogeneous to the homogeneous in the context of mass-culture and crowding (over-densification)

Train stations used to be the informal place in a city where everything that was unofficial and transient could happen. They were visually uncontrolled (a mess) and had a specific character of urban volatility, for example the Amsterdam central station and its immediate surroundings. However, today, these areas are gentrified, turned into a type of shopping malls - so called “non-spaces” according to Marc Auge. The visual chaos of informal street facades and public spaces is replaced by a new order of smooth circulation, made clean and controlled by security surveillance cameras. The fear of terrorism has also added to the process. The informal has become formal. The unofficial character has been replaced by an official one. The analysis links this observation to the concept of Heterotopia by Foucault and the concept of public domain described in ‘In search of new public domain’ by Maarten Haijer and Arnold Reijndorp in 2001.

3. authentic-fake: the notion of the real and the simulated as architectural possibilities and threats in the rehabilitation of displaced areas.

Former industrial areas are gentrified and changed into housing or areas for the so-called creative industries. In this process, are their original character and identity lost or enhanced? The NDSM wharf in Amsterdam is again an example in this case. The analysis links this observation to the concept of simulacrum and hyperreality by Beaudrillard.

4. personal-anonymous: the relationship between a place, identity and Self in the context of the twentieth century and recent suburban development.

What possibilities can architecture have as a medium to express oneself? This analysis looks at home and garden decorations, adaptation and enhancement as a means to express certain personal identity and the social-cultural position in architecture. The analysis compares Modernist, Post-modern and neo-modern architecture in their potential for appropriation, personalization and customization, relative to the concept of geno-text vs. pheno-text by Julia Kristeva. The analysis also connects to the ideas expressed in "The Practice of Everyday Life" by Michel De Certeau.

5. controlled-uncontrolled: the sequential interrelation between planned actions and their unplanned side effects in the context of the rehabilitation of the historic centre of Amsterdam.

This analysis focuses on the tension between the intended and the accidental in the context of urban design and architecture. The analysis shows the constant struggle from planners in Amsterdam to control, downsize and regulate emerging unplanned phenomena related to the speed and scale of the contemporary city (such as the increase of car traffic and pedestrian shopping crowd). In an effort to maintain an authentic quality and historical image of Amsterdam, public spaces in the city center become highly regulated and stripped of many aspects of the complexity of contemporary life, resulting in the disneyfication. In general, this perspective questions the power of accidents in architecture. Robert Venturi’s "Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture" offers a reference and also "In Search of New Public Domain" by Haijer and Reijndorp explains the concept of public domain and friction-space